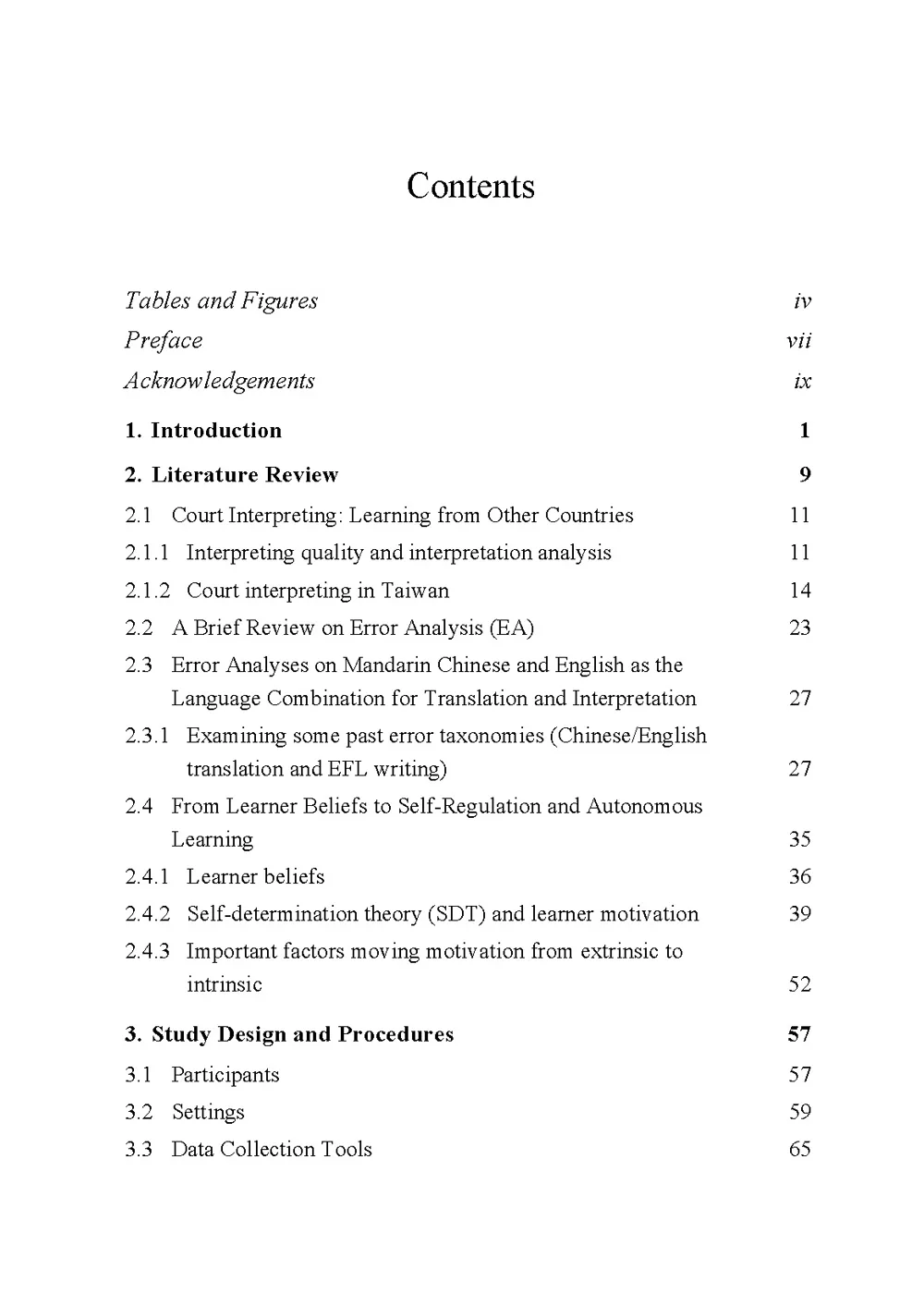

序

In Taiwan, the Judicial Yuan, the authority governing court systems and court practices, made the first formal attempt to recruit and train court interpreters in 2006. Since then, the

discipline of court interpreting has gradually attracted some researchers’ attention. Several research topics, such as the challenges faced by those in this field, quality assessment of court

interpreting, appropriate training approaches, and training materials, have surfaced in the past ten years (K. Chang, 2013, 2016, 2020; Y. L. Chen, 2018; Y. T. Chen, 2018; Chen & Chen,

2013; Tu, 2019). When observed closely, what these past studies have in common is the central idea of “the betterment of court interpreting as a practice.” When this concept is further

scrutinized, the issues of “a court interpreter’s competence to facilitate a court case” and “the quality in interpreting rendition” have emerged as two major points of discussion.

In the current practice of court interpreting in Taiwan, all details about criminal cases, either the cases at the prosecutor’s office or the cases still being processed, are kept

confidential with the main purpose of protecting the involved parties. That is, the court systems at all levels forbid any forms of recording or note-taking carried out by non-court-officials.

Consequently, it becomes extremely difficult for those who strive to improve the quality of court interpreting as there is practically no material based on which the current training content

can be improved or future training content be designed. Nevertheless, ever since the mechanism of contracted court interpreters has been put into place formally in 2008, the listed court

interpreters of different language combinations have expressed the desire of receiving more linguistic and interpreting training as well as acquiring more knowledge related to legal

cases.

This book compiles the implementation results of “Court Interpreting,” a course of specialized interpreting offered by a foreign language department at a public university in northern Taiwan.

The students taking this course have acquired basic training in translation and interpretation (T&I). The idea of course design for Court Interpreting was first formulated in 2013 with the

author’s first research project in this practice as a field. With more preparation from 2013 to 2016, the content of this course came to shape and was offered in the format of case simulation,

adopting a task-based learning (TBL) approach. So far, this course has been offered three times, and the enrollment records, with an average of 30 students, have reflected the students’ high

interest in this course. In the current development of court interpreting, with the court system’s need of more competent court interpreters, the learners’ need (the T&I students’ need) of

acquiring different interpreting training, and the interpreting instructors’ need of knowing how to better their instructional effectiveness, the scope of this study has covered two major

themes: analyzing the errors in the students’ interpreting renditions and understanding the students’ behavioral regulation styles in their engagement of the assigned learning tasks. The former

hopes to provide more information regarding the learners’ weaknesses in interpreting performances, so not only the learners can know themselves better but also the instructor will be able to

keep improving her teaching methods and materials. The latter hopes to reveal more about the factors that drive these learners’ participation and engagement in the course of Court Interpreting.

From these participating student-interpreters’ learning beliefs, attitudes, and behavioral regulation styles, more can be learned about the elements that motivate these students in their

acquisition of legal knowledge and interpreting skills. With such information in hand, more effort can be invested in training the talents needed in the field of court interpreting.