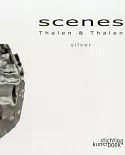

From the earliest times, learning how to construct simple and complex geometric shapes has been part of the training of a silversmith. Moreover, the educated patron of 300 years ago was also

likely to be well versed in geometry and able to appreciate the subtleties of design of a seemingly simple cream jug or sugar bowl. Many functional objects in what became known as the "Queen

Anne" style rely for effect on polygons, multi foils, ellipses, and truncated pyramids and cones.

Curiously, however, books on the history of European silver have been silent on the subject of geometry, and the process by which design is transmitted via the work bench to a finished silver

object has scarcely been explored. In his introductory essay, Christopher Hartop suggests that many of the geometric forms that became popular in the early eighteenth century were in fact

modelled on imported Asian ceramics and lacquer, some of which in turn were copying much earlier Chinese metal wares. Yet a silversmith still needed a knowledge of geometrical constructions,

whether he was copying an imported object, following a design on paper, or utilizing a template.

Using the Domcha Collection of predominantly English seventeenth- to nineteenth-century silver as examples, this important new study examines the role of geometry in the design and manufacture

of silverware. The coffeepot illustrated on the front cover is a truncated octagonal pyramid and the octofoil salveron the back flap achieves its pleasing effect through the intersection of

four ellipses with common centre. The Domcha Collection, formed during the last 25 years, shows the timeless beauty of plain silverforms, where the emphasis is on line rather than ornament. The

collection includes works by such important masters as Paul de Lamerie, Paul Crespin, Frederick Kandler and the Hennell family. Silver made in Ireland and Scotland is also featured, as is

provincial English silver made in York, Sheffield and Newcastle.