The idea of shapes whose left and right halves mirror each other across a vertical axis – the idea of symmetry, as we now usually call it - originated in Italy at the beginning of the

Renaissance. Almost immediately, it was put to use as the foundation of a bold new norm that aimed at recasting the ways in which we perceive the world and shape our habitats. The proponents of

the symmetry norm took as their starting point the premise that Nature’s forms are always symmetric and that therefore no shape can be beautiful unless it is symmetric. Within less than a

century the symmetry norm was widely acknowledged throughout western Europe. Indeed, it literally changed the face of Europe, for its enthusiasts not only insisted that henceforth all new

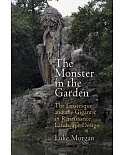

buildings must be symmetric, but also that the asymmetric facades of important medieval churches another public buildings be demolished and replaced with symmetric facades. The free-flowing and

visually-complex textures of the medieval hortus conclusus, too, were replaced by the stiff, symmetric and instantly-comprehended forms of the Renaissance garden. Since that time the authority

and scope of the symmetry norm have continued to be enlarged. It is now a byword among Classical archeologists that Greek temples are symmetric; among physicists that crystals, and most

prominently, snowflakes, are symmetric; among anthropologists, that the art of primitive peoples everywhere and at all times is symmetric; among psychologists, that humans prefer symmetric

shapes to asymmetric ones. These axioms, are all incorrect. So of course is the foundational axiom of the symmetry norm that Nature’s forms are symmetric and that only symmetric shapes can be

beautiful. The effect of the symmetric norm was thus not only to change the appearance of Europe but to enervate significant aspects of Western cultural and intellectual life. The Notes in this

book aim at tracing the origin, survival and consequences of these fallacies.