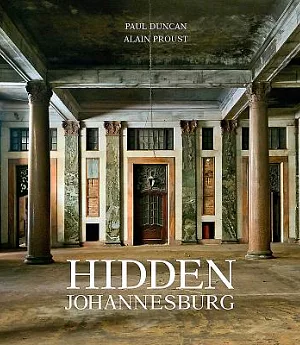

In Hidden Johannesburg, Paul Duncan provides a snapshot of 28 of the city’s architecturally and culturally significant buildings, alongside superb photography from Alain Proust. Some date from

the early 20th century, when Johannesburg was transforming itself from mining camp to modern metropolis. Others speak to the influences that shaped the city: cultural, ethnic, historical,

religious and commercial. There are churches and cathedrals, synagogues and mosques, as well as schools, homes, places of business and even a prison.

Sir Herbert Baker and his partners had a hand in many notable buildings that predate WWI: the cloistered quads and crypt of St John’s College Houghton; Glenshiel in Westcliff, now the

headquarters of the Order of St. John; legendary Northwards in Parktown, once owned by randlord John Dale Lace and his socialite wife Josie; Bedford Court, home of mining magnate Sir George

Farrar and now part of St Andrew’s School for Girls; and Villa Arcadia, a Parktown mansion built to the exacting standards of Florence Phillips; St. George’s Parish Church in Parktown, and St.

Michael and All Angels in Boksburg.

Places that speak of another life and time, or capture the spirit of occupants long gone include Nelson Mandela House in Vilakazi Street, Orlando West, where he lived from 1946 until his arrest

in 1962, now a museum that attracts visitors from all over the world. Satyagraha House, in Orchards, was home to Mahatma Ghandi. In nearby Kew was the home and studio of sculptor Edoardo Villa

and many of his works are still in situ.

Anstey’s was once a glamorous department store. Completed in 1936 in the Art Deco style and, for a time, the tallest building in Johannesburg, it survives as an apartment block. Gleneagles, in

Killarney, of similar style and vintage, has become another sought-after residence.

There are also newer buildings whose architects have sought to integrate form and function. The Nizamiye Masjid in Midrand stands out, and not just because of its tall minarets; St Charles

Borromeo Catholic Church in Victory Park.

Given Johannesburg’s reputation for tearing down anything ‘old’, it is remarkable how much of the city’s heritage remains; yet there is always the threat of demolition. Hidden Johannesburg

shines a spotlight on places not accessible to the ‘ordinary’ person and invites us to consider the impact of the built heritage in shaping our cities. By affording us a glimpse of our past,

perhaps it will help to shed light on our future.