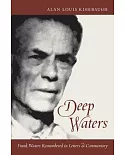

Robert Frost and Edward Thomas met in a bookshop in London in 1913. During the next four years, the two writers��rost, an unknown poet who had sold his farm in New Hampshire in order to take

his family to England for one last gamble on poetry and Thomas, a sad literary journalist��ormed the most important friendship between poets since that of Wordsworth and Coleridge. Their

friendship only ended with Thomas' death in Arras, France, a casualty of the First World War.

The story of Edward Thomas' turn to poetry, in fact, has been dominated by the account of Robert Frost's injunction: to break his existing prose into lines, bringing his musical cadence and his

direct speaking voice into conversation with formal prosody. Thomas himself had already championed Frost's own early work: These poems are revolutionary because they lack the exaggeration of

rhetoric.... Their language is free from the poetical words and forms that are the chief material of the secondary poets. The metre avoids not only old fashioned pomp and sweetness, but the

later fashion also of discord and fuss. In fact the medium is common speech.... Mr. Frost has, in fact, gone back, as Whitman and as Wordsworth went back, through the paraphernalia of poetry

into poetry once again.

This book presents for the first time the full record, arranged chronologically, of what the poets wrote to, for, and about one another��heir letters, poems, and Thomas' review of Frost's first

two books. They reveal a warmth and charm that give us the key to the relationship between Frost and Thomas.